When Brad Wang landed his first tech job straight out of college, he was struck by the indulgent perks of Silicon Valley. Game rooms, nap pods, and scenic hiking trails turned the mundane concept of work into something that felt more like a Gatsby-esque gathering. For a newcomer like Mr. Wang, it was an impressive spectacle.

Beneath the glamorous surface, however, he found a troubling emptiness. Moving between software engineering roles, he often found himself working on projects that seemed pointless. At Google, he spent over a year on an initiative that leadership acknowledged would never launch. Later, at Facebook, he contributed to a product a key client bluntly described as useless.

The futility of his efforts became increasingly frustrating for Mr. Wang. “It felt like baking a pie just to throw it straight into the trash,” he remarked.

This sense of purposelessness is far from new in the corporate world. For decades, workers have questioned the value of their daily grind. During the pandemic, thousands flocked to the r/antiwork subreddit to voice discontent with monotonous jobs or, in some cases, work itself. The 1990s cult classic “Office Space” lampooned corporate drudgery, immortalizing the line, “It’s not that I’m lazy, it’s that I just don’t care.” And long before that, Herman Melville’s Bartleby, the Scrivener introduced us to the archetypal quiet quitter, a clerk who defies his boss with a simple, recurring refrain: “I would prefer not to.” Eventually, Bartleby’s passive rebellion leads to his demise, but his story lives on as a stark critique of meaningless work.

The corporate world, with its endless paperwork and routines, has a knack for transforming even desirable jobs—those with good pay, benefits, and comfortable environments—into draining, soul-crushing experiences.

In 2013, radical anthropologist David Graeber offered a new perspective on this issue in his essay, On the Phenomenon of Bullshit Jobs. This sharp critique of capitalism, penned by the same thinker behind Occupy Wall Street’s “99 percent” slogan, quickly went viral, resonating with widespread disillusionment in the modern workforce. Graeber later expanded the essay into a book that explored the concept in greater depth.

Graeber argued that economist John Maynard Keynes’s vision of a 15-hour workweek never materialized because society has created countless jobs so pointless that even those performing them struggle to justify their purpose. Supporting this claim, a study by Dutch economists Robert Dur and Max van Lent found that a quarter of workers in wealthy countries consider their jobs potentially meaningless. If these roles demoralize employees and offer no real value to society, Graeber asked, why do they still exist?

The urgency of this question has grown with the rapid advancement of artificial intelligence, raising concerns about job displacement. Goldman Sachs estimates that generative A.I. could potentially automate tasks equivalent to 300 million full-time jobs worldwide, particularly in office roles such as administration and middle management.

When envisioning a future where technology replaces human labor, the narrative often swings between two extremes: a productivity windfall for businesses and a bleak scenario for workers rendered obsolete. However, there’s a middle ground to consider—one where A.I. eliminates jobs that workers already find meaningless or even degrading. If this happens, could it actually improve the lives of those workers?

David Graeber’s exploration of “bullshit jobs” offers some insight. He categorized certain roles as inherently useless, such as “flunkies,” who exist solely to enhance the status of the wealthy; “goons,” whose positions are created in response to competitors; and “box tickers,” whose work feels redundant or inconsequential. Economists have refined these ideas, identifying jobs deemed useless by the workers themselves—roles that, if erased, would have little to no impact on the world.

Artificial intelligence, with its prowess in pattern recognition, is well-suited to automating repetitive tasks like drafting emails, reviewing legal documents, or translating languages. While humans often struggle with monotony, leading to mistakes or fatigue, A.I. tirelessly performs such tasks without losing focus. This overlap between A.I.’s capabilities and so-called meaningless work raises the question: Could A.I. not only boost efficiency but also liberate workers from jobs they themselves regard as pointless?

An obvious target for “flunky” automation is the executive assistant. Tools like IBM’s A.I. assistant and Gmail’s auto-reply already streamline administrative tasks, while startups like Duckbill go further, handling to-do lists from returning purchases to buying gifts—chores once delegated to secretaries in the “Mad Men” era.

A.I.’s presence in administrative work has arrived, a reality that hit Kelly Eden, a 45-year-old writer, hard. She supplemented her income with tasks like drafting emails, earning 50 cents per word from a chocolatier client. This year, the client switched to ChatGPT, leaving Eden scrambling for a backup plan to support her writing career.

Telemarketing, labeled a “goon” job by David Graeber, is also being replaced. Workers often sell products they know customers don’t need—an ideal task for chatbots, which handle rejection and surly customers without complaint. Companies like AT&T are already using A.I. to script customer service calls, leaving some employees feeling like they’re training their own replacements.

Even software engineering isn’t immune, with some tasks veering into “box ticking” territory. Brad Wang experienced this firsthand, writing code that never went live, a project he believed served only to bolster his bosses’ careers. He recognizes that much of this could also be automated.

Despite their perceived lack of purpose, these jobs provide stable incomes and act as gateways to white-collar careers, offering training and mobility for workers. Economists warn that as A.I. replaces these roles, the new jobs that emerge may bring lower pay, fewer growth opportunities, and even less meaning.

“Even if we accept Graeber’s perspective on meaningless jobs, eliminating them should still concern us,” said Simon Johnson, an economist at M.I.T. “This is the hollowing out of the middle class.”

A ‘Species-Level Identity Crisis’

The future labor market in an A.I.-dominated world is difficult to predict. While automation may displace workers in certain roles, history shows that technology often creates new opportunities. The shift from horse-drawn carriages to cars generated jobs in manufacturing, sales, and maintenance. Similarly, personal computing eliminated millions of jobs but spurred entirely new industries that were unimaginable a century ago, highlighting why John Maynard Keynes’s 1930 prediction of 15-hour workweeks remains unrealized.

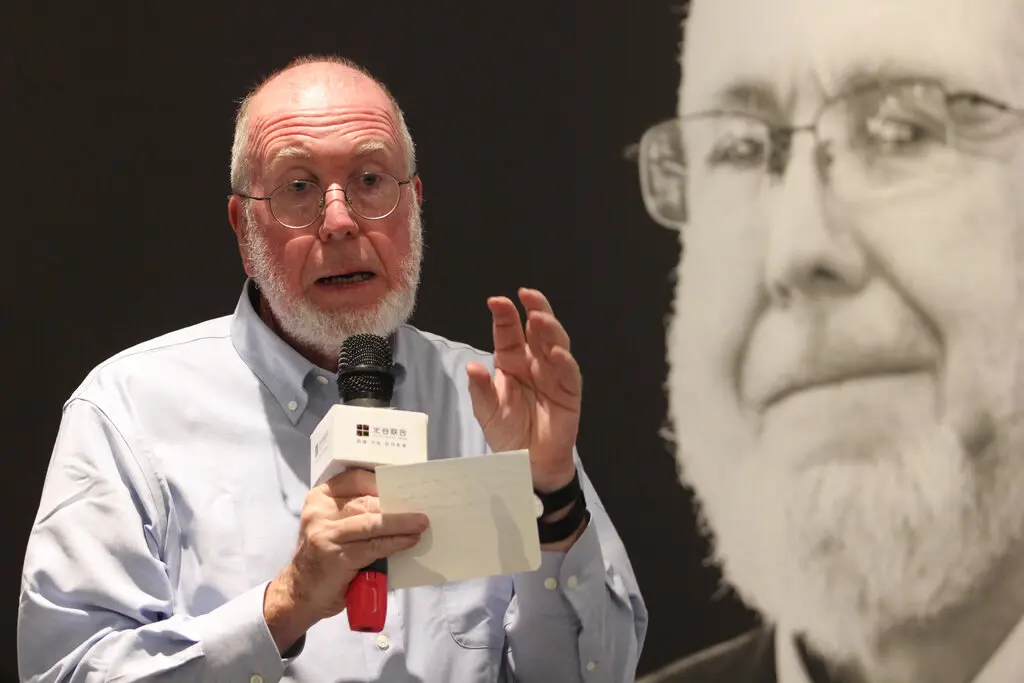

Kevin Kelly, co-founder of Wired and author on technology, expresses cautious optimism about A.I.’s potential impact on meaningless work. He believes it may encourage workers to explore deeper questions about what constitutes a fulfilling job.

Kelly describes a psychological cycle of job automation. At first, workers doubt that machines can replicate their tasks. Over time, they concede machines can, but only with human intervention. Eventually, they recognize that some jobs were better suited for automation and find more meaningful pursuits. This cycle culminates in the realization: “I’m glad a robot cannot do what I do.”

Realizing your job can be replaced by technology is disheartening, highlighting its lack of meaning. However, it can also push individuals to reflect on their goals and pursue more fulfilling, exciting opportunities.

Kevin Kelly believes that automation can highlight the lack of meaning in certain jobs, pushing people to ask deeper questions about their purpose. “It might make certain things seem more meaningless than they were before,” he said. “What that drives people to do is keep questioning: ‘Why am I here? What am I doing? What am I all about?’” While these are challenging questions, Mr. Kelly considers them essential. “The species-level identity crisis that A.I. is promoting is a good thing,” he added.

Some scholars suggest that these crises could inspire people to pursue more socially valuable work. Dutch historian Rutger Bregman has spearheaded a “moral ambition” movement in the Netherlands, where groups of white-collar workers meet to encourage each other to transition into more meaningful roles. Modeled after Sheryl Sandberg’s “Lean In” circles, the movement also offers fellowships for individuals to take on socially impactful jobs, such as combating the tobacco industry or promoting sustainable foods.

“We don’t start with the question of ‘What is your passion?’” Mr. Bregman explained. “Gandalf didn’t ask Frodo, ‘What’s your passion?’ He said, ‘This is what needs to get done.’”

In the A.I. era, the immediate focus is expected to shift toward oversight rather than innovation, says David Autor, an M.I.T. economist specializing in technology and jobs. Companies will increasingly need “A.I. babysitters”—humans who review, edit, and manage A.I.-generated content, from legal documents to marketing copy, while keeping the technology’s occasional “hallucinations” in check. Some jobs may benefit from this division of labor, with A.I. handling repetitive tasks and humans tackling more complex ones, as seen in radiology, where machines interpret standard scans, and doctors handle exceptions.

However, many workers may find themselves performing tedious error-checking on A.I.-produced outputs, which could fail to resolve feelings of pointlessness. “If A.I. does the work, and people babysit A.I., they’ll be bored silly,” warns Autor.

Jobs rooted in empathy and connection are also at risk. Machines don’t tire of faking empathy or absorbing customer frustration, making them prime candidates for roles in customer service and other “connective labor” fields. While this spares humans the emotional toll, it also removes the moments of joy these jobs can bring. Sociologist Allison Pugh notes that technology has already degraded empathic professions like therapy or chaplaincy, reducing meaningful interactions. Grocery clerks, for instance, have lost personal connections with customers as automated checkouts dominate, leaving them to handle frustrations instead.

Even techno-optimists like Kevin Kelly acknowledge the inevitability of meaningless jobs, arguing that, as per David Graeber’s definition, meaninglessness ultimately lies in the eye of the worker. As A.I. reshapes the labor market, the challenge will be creating roles that preserve a sense of purpose and fulfillment.

Even outside of David Graeber’s framework of meaningless work, many people have conflicted feelings about their jobs. Over time, the monotony of doing the same tasks, taking orders that seem illogical, and being just a small part of a larger system can lead to frustration. These feelings may persist even as workers take on new roles created by A.I., which continues to automate some responsibilities while introducing others to manage the technology.

While some workers will seek out entirely new opportunities, others may choose to reshape their current roles, finding meaning in improving their workplaces and supporting colleagues. Broader solutions like universal basic income, championed by figures like Graeber and OpenAI’s Sam Altman, also offer a potential answer to the challenges work presents in an A.I.-driven economy.

Ultimately, A.I. amplifies existing labor issues rather than solving them. It transforms the nature of work but doesn’t resolve people’s complex relationships with it. In Silicon Valley, Brad Wang predicts that automating pointless tasks won’t eliminate ambition but may drive engineers to get even more creative in chasing promotions. “These jobs rely on selling a vision,” he said. “And that’s one problem you can’t automate.”

Nguồn: https://www.nytimes.com/2024/08/03/business/ai-replacing-jobs.html?searchResultPosition=51#