Historical economic trends reveal that unemployment rates often begin to rise before a recession hits, while widespread layoffs tend to follow as the downturn deepens.

As job growth slows and unemployment edges higher, some economists see a glimmer of optimism in employers’ reluctance to part with their current workforce. Despite high-profile layoffs at a few major companies, overall job cuts remain below pre-pandemic levels during times of economic strength. Even unemployment benefit claims, which rose earlier this year, have been trending downward recently.

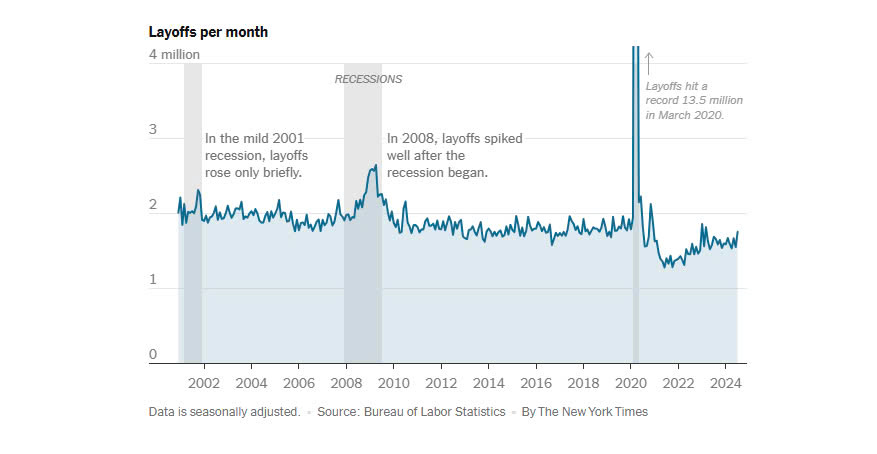

However, history warns against placing too much confidence in layoff statistics alone. In past recessions, significant job cuts have typically occurred only after an economic downturn has firmly taken hold. This pattern suggests that the labor market’s current resilience may not be as reassuring as it appears.

The Great Recession serves as a notable example of this pattern. Officially starting in late 2007 following the housing bubble burst and the mortgage crisis, unemployment rates began to climb in early 2008. However, widespread job cuts did not take hold until late 2008, after the collapse of Lehman Brothers and the escalation of a global financial crisis. This timeline illustrates how layoffs often lag behind the initial signs of an economic downturn.

The milder 2001 recession highlights this dynamic even more clearly. While the unemployment rate climbed steadily from 4.3% in May to 5.7% by year’s end, layoffs remained relatively stable, apart from a brief spike in the fall.

This pattern has been consistent across earlier recessions, and economists cite a simple explanation: layoffs are often disruptive, costly, and detrimental to employee morale. As a result, companies tend to avoid cutting jobs unless absolutely necessary, sometimes delaying layoffs even beyond what financial logic might suggest.

“It’s costly to lay someone off,” noted Parker Ross, global chief economist at Arch Capital. “That’s something that generally firms turn to as a last resort.”

This reluctance is particularly pronounced now, as many employers faced significant challenges hiring after the pandemic recession. According to Ross, even if business slows, companies may choose to hold onto their workers to avoid the risk of being understaffed if the economy rebounds. This hesitancy underscores a new dimension of employer decision-making in today’s labor market.

Employers’ reluctance to lay off workers is reassuring for now, but it comes with a potential downside: if the economy deteriorates beyond what businesses expect, companies may suddenly need to reduce their workforce. Such abrupt layoffs could trigger a downward spiral—job losses leading to reduced consumer spending, which in turn fuels further job cuts.

“That’s what everybody worries about, because unemployment begets unemployment begets unemployment,” said Andrew Challenger, senior vice president at Challenger, Gray & Christmas, a firm specializing in labor market analysis.

Interestingly, unemployment doesn’t always spike due to massive layoffs. Instead, what often defines a recession is a significant slowdown in hiring. This perspective challenges the common association between recessions and widespread job losses. Layoffs happen even in robust economies, but during downturns, those who lose their jobs face prolonged difficulties in finding new opportunities.

“When a hiring manager decides not to fill a position, that doesn’t tend to make headlines,” explained Robert Shimer, an economist at the University of Chicago. However, these quiet decisions—amplified across the economy—can significantly contribute to rising unemployment. In a 2012 study, Shimer found that about three-quarters of unemployment fluctuations stem from changes in the hiring rate, highlighting its critical role in labor market dynamics.

In other words, hiring trends, rather than layoffs, are often the key indicator of a potential recession—and hiring has already slowed noticeably.

Over the past three months, employers added an average of just 116,000 jobs per month, a significant drop from the 451,000 jobs added during the same period two years ago. Gross hiring—the total number of people brought on board, regardless of separations—has also declined, falling to approximately 5.5 million jobs per month from a peak of nearly seven million in early 2022.

This shift marks a departure from 2022, when employers were scrambling to fill positions after the pandemic-induced labor shortages. A slowdown from that frantic pace was expected, but recent months have seen hiring dip below pre-pandemic levels. Research from the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis suggests this decline has contributed to a modest uptick in the unemployment rate, which rose to 4.2% in August, up from a historic low of 3.4% earlier in 2023.

Still, economists urge caution in interpreting these trends. The current slowdown in hiring does not necessarily signal that a recession has begun or that one is inevitable. The post-pandemic economy continues to defy certain pre-pandemic patterns, and while the labor market has weakened, it remains strong by many metrics.

Despite the overall strength of the labor market, there are growing signs that job seekers are facing more challenges. The percentage of unemployed workers successfully finding jobs each month has declined, and the number of long-term unemployed—those out of work for more than six months—has increased. Survey data also reflects a dip in worker confidence, with many feeling less certain than last year about their ability to quickly find a new job if they were to lose their current one.

“Businesses have pulled back,” said Mr. Ross of Arch Capital. “There’s not as much demand for labor, and they’re not hiring at the pace they were.”

These trends suggest a shift in the hiring landscape, adding to concerns about the overall direction of the labor market.