Job growth has decelerated, yet unemployment continues to defy traditional economic expectations. Significant policy shifts under the new administration may challenge this stability.

Not long ago, the pivotal question driving economic forecasts and financial market speculation was this: Can the U.S. economy sidestep a recession?

Today, for many in the business world, that question feels almost outdated—a remnant of a more anxious narrative.

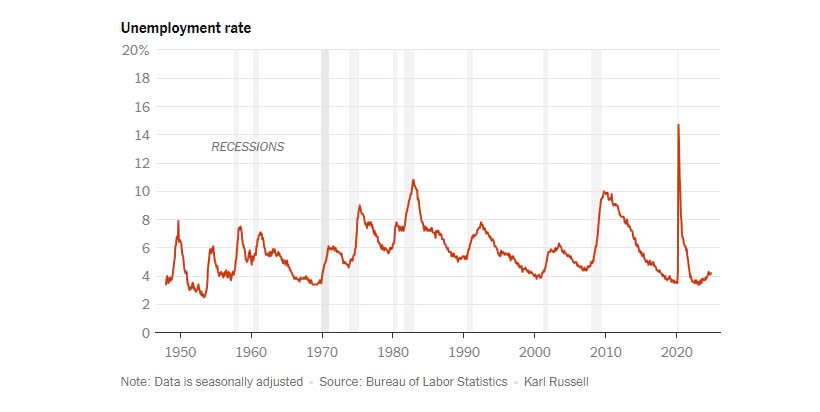

After more than two years of maintaining an unemployment rate below 4 percent, it has now edged up to 4.2 percent since last spring. While hiring has slowed, layoffs remain notably low by historical standards, with December’s data expected on Friday.

Inflation, though significantly tamed, remains under the Federal Reserve’s watchful eye. Having aggressively raised interest rates in 2022 to counter price hikes, the Fed pivoted in late 2024. At three consecutive meetings, it made modest rate cuts, aiming to ease pressure on commercial activity and lend support to the job market.

As 2025 begins, the economic landscape remains steady yet cautious. While fears of an immediate recession with widespread layoffs have mostly faded, analysts continue to assess emerging risks with unease.

President-elect Donald J. Trump has fueled uncertainty by reiterating threats of imposing sweeping global tariffs — import taxes that economists warn could reignite inflation if implemented abruptly. Additionally, his campaign promises of aggressive deportations of undocumented immigrants and stricter border controls leave questions unanswered. If these policies are pursued to their fullest extent, they could significantly impact hiring and labor availability in key industries.

Much of the lingering uncertainty surrounding the labor market’s trajectory stems less from potential political disruptions and more from growing doubts about the predictable patterns of the business cycle.

There is cautious optimism among Wall Street fund managers and labor economists that hiring could remain stable and that, against historical trends, the unemployment rate might hold at its remarkably low levels for the foreseeable future.

Historically, economic growth in the United States has followed a familiar wave-like pattern: businesses, buoyed by over-optimism, expand too far and eventually pull back on investment and hiring. Consumer confidence declines as jobs become harder to find, leading to reduced spending and production. This phase typically sees an increase in bankruptcies and unemployment. Eventually, as debts are resolved, optimism returns, spurring lending, spending, and the start of a new growth cycle.

However, the last classic example of such an economic cycle occurred from 2002 to 2007, ending in the devastation of the financial crisis. Since 2009, the only recession the U.S. has experienced was triggered by the unprecedented shock of a global pandemic, not internal economic imbalance.

As the current decade began, there was little sign of immediate danger to the economy. In February 2017, shortly after Mr. Trump assumed office, the unemployment rate was 4.6 percent. By February 2020, just before the pandemic lockdowns, it had fallen to 3.5 percent, a level that reflected one of the strongest labor markets in recent history.

Some prominent voices in finance, such as David Kelly, chief global strategist at JPMorgan, and Rick Rieder, a top fund manager at BlackRock, have recently doubled down on their bold assertion that the traditional business cycle, as it was once understood, no longer holds sway. They suggest that the labor market is likely to settle into a similarly stable rhythm, even if unemployment doesn’t reach the record lows of previous years.

Their argument hinges on the idea that the cyclical fluctuations of manufacturing and agriculture—industries that once dominated the U.S. economy—are less relevant today. Now, around 70 percent of the American economy is driven by consumer spending, primarily directed at services that maintain steady demand.

“We expect the economy to add an average of 150,000 to 175,000 payroll jobs per month in 2025,” Mr. Kelly wrote in a client note this week. He also emphasized that, barring a severe immigration crackdown, foreign-born workers should be able to meet labor demand, keeping the unemployment rate near 4 percent.

While Mr. Kelly acknowledged that the economy is not “invulnerable,” he highlighted the optimism surrounding artificial intelligence, which has spurred business investment, stock market gains, and a rise in labor productivity. He believes this enthusiasm will continue to drive capital spending.

However, other labor market analysts express caution. Skanda Amarnath, executive director of Employ America, a research group focused on industrial data and full employment, warns that the A.I.-fueled tech boom could backfire. If the surge in Corporate America’s tech spending becomes either saturated or overextended, it could lead to a downturn, dampening the economic momentum tied to A.I. advancements.

If such a downturn were to occur, it could signal a reawakening of the traditional business cycle after an extended period of calm.

“The more near-term upside we experience in 2025, the greater the chance of a deeper recession in the future,” said Skanda Amarnath, executive director of Employ America. “Macroeconomic shocks often echo past crises, yet they remain exceptionally hard to predict.”

One potential risk of artificial intelligence, which has driven much of the recent economic optimism, is its impact on labor. While previous waves of technological advancement generally complemented human work, A.I. could replace jobs at a much faster pace if its development accelerates in the coming years.

“Earlier rounds of I.T. advancements supported labor, but A.I. is likely to displace workers more aggressively,” said Samuel Tombs, chief U.S. economist at Pantheon Macroeconomics.

Even now, not all labor market indicators are shining. For example, the hires rate—a key measure of labor market activity that calculates hiring as a share of overall employment—has dropped to levels last seen in 2013, when the unemployment rate exceeded 7 percent. This decline raises questions about the current strength of the labor market, despite low overall unemployment.

In essence, while employment levels remain high, those seeking jobs are finding it increasingly difficult. The labor market sits in a peculiar state of limbo, with hiring subdued but layoffs still remarkably low. Typically, when unemployment begins to rise from its cycle low, it doesn’t linger near that level but instead spikes sharply before gradually easing back.

When asked whether unemployment is more likely to climb to 5 percent before dropping back to 4 percent, as historical trends and economic theory suggest, Peter Williams, economist and managing director at 22V Research, admitted, “I’m quite torn.”

He acknowledged the year’s “robust starting point” and the Federal Reserve’s ability to lower interest rates further if needed. However, signs of trouble remain, such as the sluggish housing market.

“At the same time,” he noted, “there are so few vulnerabilities in the economy right now that it’s hard to see how taking a couple of steps back would be enough to truly derail things.”