The post-pandemic recovery has led economists to question whether their strategies need a complete rewrite or simply an added chapter.

The pandemic triggered an unprecedented economic crisis, defying comparisons to any previous recession. Unsurprisingly, its aftermath has also unfolded in ways that caught many economists off guard.

When unemployment skyrocketed during the pandemic’s early days, fears mounted of a repeat of the protracted, sluggish recovery seen after the Great Recession. That period left deep scars on countless workers. Yet, against all odds, the labor market has bounced back in record-breaking fashion.

By early 2021, some economists predicted a wave of inflation. Skeptics dismissed these warnings, citing recent years’ failed forecasts, often from the same voices. This time, however, the predictions came true.

As the Federal Reserve moved to curb inflation, many warned of inevitable job market turmoil, a familiar outcome when interest rates climbed rapidly in the decade before the pandemic. Yet, despite the Fed’s push to the highest rates in decades, the job market has remained remarkably stable, even showing signs of renewed momentum.

While the story of this recovery is far from over — and a “soft landing” isn’t guaranteed — one thing is clear: the economy, and particularly the labor market, has shown a resilience few thought possible.

Interviews with dozens of economists, ranging from those who partially anticipated the recovery to those who missed the mark, offer valuable lessons from the past two years. While they differed on specifics, three overarching themes stood out.

This time truly stood apart

Economists often hesitate to declare, “This time is different,” as history has shown that the core principles of economic cycles tend to persist: bubbles eventually burst, debts must be paid, and trends in employment follow patterns that, while imperfect, remain broadly predictable.

Yet, the pandemic-induced recession truly defied precedent. Unlike past downturns rooted in systemic economic imbalances—like the dot-com bubble of the early 2000s or the subprime mortgage crisis a few years later—this crisis stemmed from a global health emergency that brought entire industries to a halt almost overnight.

The response was equally unprecedented. The federal government unleashed a wave of financial aid on a scale never seen before, reaching households and businesses across the country. Remarkably, even as unemployment soared, personal incomes rose in 2020.

The outcome was a recovery marked by speed and disorder. Once vaccines became widely available, people were eager to resume spending, buoyed by the financial cushions they had received. However, businesses were caught off guard. Many had downsized their workforces, losing employees who had moved away, shifted to other sectors, started their own ventures, or opted out due to lingering health concerns or closed schools.

Compounding the challenges, supply chains remained tangled long after daily routines began to normalize. Companies had to adapt not only to logistical bottlenecks but also to shifts in consumer schedules, spending habits, and behaviors reshaped by the pandemic. The result was a recovery unlike any in modern history.

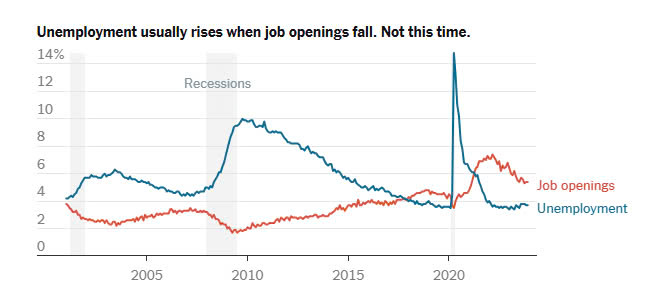

Looking back, it seems almost self-evident that the usual economic principles might not hold in such extraordinary circumstances. Typically, a drop in job openings leads to a rise in unemployment—fewer opportunities make it harder to find work. Yet, in the wake of the pandemic shutdowns, even as the initial hiring frenzy waned, job vacancies outpaced the number of available workers. Companies, having struggled to hire during the recovery, were reluctant to let employees go, keeping layoffs low despite a cooling demand.

Some economists anticipated that the pandemic economy might break conventional patterns. For instance, Christopher J. Waller, a Federal Reserve governor, suggested in 2022 that job openings could decline without necessarily triggering higher unemployment. However, many others were slower to recognize how standard economic models failed to capture the unique dynamics of the pandemic economy.

“It’s risky to forecast during extreme periods using linear relationships derived from normal times,” noted Laurence M. Ball, an economist at Johns Hopkins. “We should have seen that coming.”

The job market is returning to normal — and normal is pretty good

The job market no longer seems unusual. In many ways, it resembles the pre-pandemic landscape. Job openings are slightly higher than in 2019, turnover is a bit lower, and the unemployment rate is nearly identical.

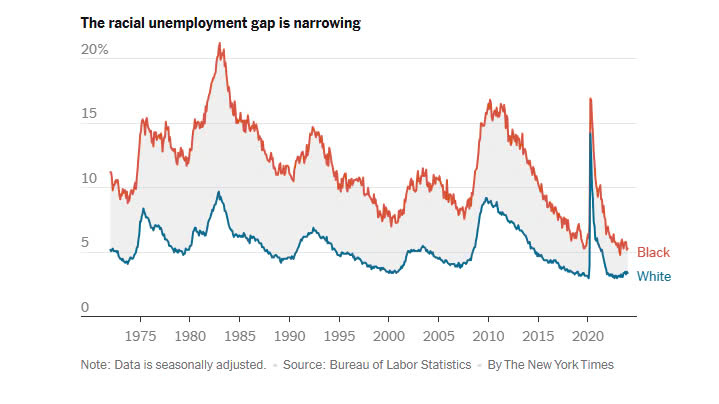

The encouraging news is that 2019 was an exceptionally strong labor market, with benefits reaching across racial and socioeconomic divides. By some measures, the 2024 labor market is even more robust. The unemployment gap between Black and white Americans is approaching a record low. Job opportunities have expanded for individuals with disabilities, those with criminal records, and people with limited formal education. Additionally, wages are rising across all income levels and, with inflation under control, are now outpacing price increases.

“Normal” in 2024 has undeniably shifted from what it meant five years ago. The pandemic prompted millions to opt for early retirement, with many choosing not to return to the workforce. Meanwhile, the rise of remote and hybrid work has reshaped demand, reducing the need for services like dry cleaning while shifting others, such as weekday dining, from urban centers to suburban neighborhoods.

While these shifts continue to unfold, the frenzy of rehiring and rapid reallocation has subsided. Workers are still moving between jobs, but the days of casually leaving during lunch to accept a higher-paying offer just down the street are over. Similarly, employers still face hiring challenges, but the era of lavish signing bonuses and double-digit wage increases to lure employees has largely passed.

As a result, many economic principles that seemed irrelevant during the recovery are beginning to regain relevance. For example, with fewer unfilled positions, a decline in job openings might once again signal a rise in unemployment. Although older models may not fully capture today’s complexities, they are becoming more applicable.

“We’ve experienced a period where a lot of unusual things occurred,” said Guy Berger, director of economic research at the Burning Glass Institute, a labor market research organization. “But now we’re transitioning back to a world that feels more familiar.”

The good times don’t have to come to an end — at least, not yet

A few years after the Great Recession ended, economists began cautioning that the United States might soon face a labor shortage.

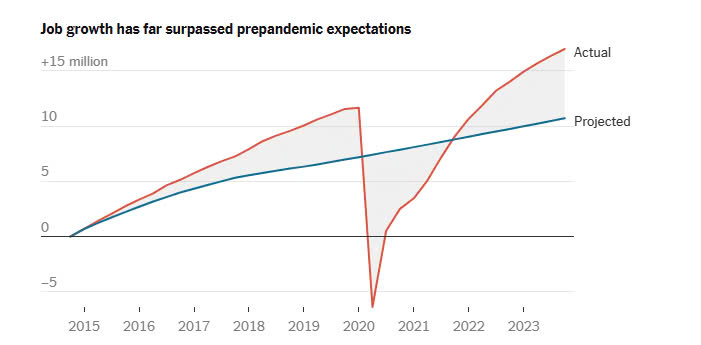

Employment levels had exceeded their pre-recession peak, and the unemployment rate was nearing 5 percent—a threshold many economists considered indicative of full employment. During the recession, millions had left the labor force, leaving uncertainty about how many were willing or able to return to work. In early 2015, the nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office projected that job growth would soon taper off, keeping pace only with population growth.

Those projections turned out to be far too pessimistic. Between the end of 2014 and the end of 2019, U.S. employers added over 11 million jobs—millions more than the Congressional Budget Office had anticipated. Companies began hiring workers they had previously overlooked, driving the unemployment rate to a 50-year low and raising wages to draw people back into the labor force. At the same time, businesses found ways to boost worker productivity, enabling growth without needing to expand their workforce as much.

Had the pandemic not occurred, job growth from those years might have eventually slowed. However, there was little indication in early 2020 that such a slowdown was imminent, and there’s no clear reason it must happen now in 2024.

“A strong labor market creates a virtuous cycle,” said Julia Pollak, chief economist at ZipRecruiter. “People have jobs, they spend money, companies thrive, and they hire even more workers. It takes something significant to disrupt that momentum.”

That disruption remains a possibility. The Federal Reserve, wary of inflation, might wait too long to lower interest rates, potentially triggering a recession. Additionally, recent data may have painted an overly rosy picture of the job market’s health, with some economists pointing to subtle signs of underlying fragility.

Still, similar warnings about cracks in the economy have been circulating for over a year. Thus far, the foundation has remained remarkably strong.

Source: https://www.nytimes.com/2024/02/14/business/economy/lessons-job-market.html?searchResultPosition=34